Short and Sweet

First rule of prepping a Land Rover for overland travel? Don’t buy a short-wheelbase. Except that’s exactly what Gareth Griffiths did – and he was totally satisfied with the results.

We’re a fickle lot, us human beings. We’re forever changing everything, from the ringtones on our mobiles to the style of clothes we wear. Just about the only thing you can be sure of with Modern Man is that you can’t be sure of anything. When it comes to trucks, us blokes like nothing more than to find one we like, get it the way we want it… then change it for another one.

Gareth Griffiths is the exception. The 90 in these pictures was only the third he had owned when we took them: some Landy-loving types have been known to buy that many all in one go, let alone in a lifetime.

What makes this 90 rare, however, is that when you buy a Defender to prep for overland travel you tend to go for a 110 or 130. The 90? It’s just too small.

Gareth’s previous Landies were a IIA Lightweight and an earlier 90, but for his expedition truck he wanted something with power steering and a more reliable engine. What he got was a 1996 300Tdi County Hard-Top with three previous owners.

‘The vehicle was bought from new and owned for most of its life by a lady who wanted something to take her dogs about in,’ he explains. ‘I still have the original receipt. Dealer maintained and serviced, and only genuine parts fitted, it then went through two chaps in the space of three or four years who didn’t use it much but looked after it well – at which point I bought it.’

That was in May 2008, and Gareth didn’t waste any time in getting to grips with his new truck. Before the engine had cooled down, he’d stripped off the roof rack, side steps and County decals – and by October of that year, he took his first solo trip to Morocco.

Gareth says he started learning a lot about fixing Land Rovers very soon after buying his first 90, which is something a lot of people will be familiar with. It might make him sound like a bit of a driveway dreamer, but nothing could be further from the truth.

Aside from the roll cage, which was made and fitted by Whitbread Off-Road, everything on the 90 was put there by Gareth himself. Having

replaced the original springs and shocks with a two-inch Terrafirma lift, he was able to slide a set of 255x85R16 BFGs on Wolf rims under the wheelarches, and he followed this up with a modified Warn M8000 on an ARB front bumper. ‘The internals,’ he continues, ‘all happened around these and continued after.’

And what would those internals be? ‘You name it, we carry it!’ Here, we’re getting into the reason why 110s are a much more common sight than 90s on the overland trail. But Gareth is happy with the mods he’s made, insisting that the shorter vehicle has enough space to be a fully functional home-from-home. As is always the case with real-world expedition vehicles (as opposed to the kind you see at shows with millionaire price tags on them), it’s not all pretty, or in any way high-tech, but it’s very much about fitness for purpose and making the most of every scrap of space.

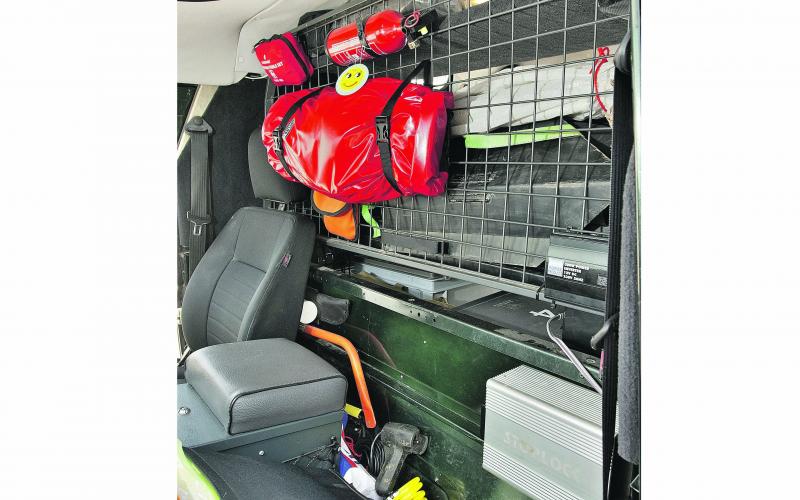

Hence the dog guard behind the seats, which is home to a 300-Watt inverter, first aid kit, fire extinguisher and bug-out bag. Wot-out bag? A bug-out bag is a self-contained survival kit for proper emergencies. If your Land Rover’s on fire, under water or being driven away by gorillas, a bug-out bag is the thing you grab as you’re running for your life. Its job is to ensure that by escaping the immediate threat, you’ve not just consigned yourself to a slower fate instead.

Less likely to save any lives, but equally valuable in their own way, the original seats have been re-foamed and then trimmed with Outlast fabric from Exmoor Trim. The cabin is further augmented by a 14-inch Mountney steering wheel, while a Mud-UK dash console and Mobile Storage Systems cubby box look after extra gauges and general oddments respectively. Strapped to the dash is a Hewlett Packard tablet PC which runs various mapping packages, and plays music, DVDs and computer games – ideal for those long nights under canvas.

Out the back, there’s a neat storage system made up using Mantec load slides, with a shelf mounted on aluminium channel to just clear a slide-out Engel fridge. Gareth finished off the sides using plywood and marine grade carpeting, adding extra cargo nets at the same time. Up top, another shelf carries a pair of loudspeakers and everyday clothes.

The recovery kit lives in a pair of canvas holdalls, electronic equipment is stored in Peli cases, camping gear goes in a pair of Zarges boxes and everything else is housed in a variety of heavy-duty Plastor containers. With so many different sizes and other options being available, he points out that this setup is infinitely adaptable to suit every expedition: ‘As we use a boxed system over fixed drawers, we have an adaptable approach to each trip and so don’t carry any unnecessary weight.’

He doesn’t take any unnecessary risks, either. Protecting it all, which is essential when overlanders are all too often seen as easy prey, is a set of MSS window grilles.

As you’ll have worked out by now, Gareth’s 90 is very much a home-grown expedition truck. The way it’s been put together is what makes it unique, with all its owner’s quirks and preferences built in. Ask even the best expedition prep specialist to build you a chequebook overland vehicle and however hard they try, that’s something you’ll never get.

You’ll not get a 90, either, unless that’s what you specifically ask for – in which case you’ll receive an attempt to talk you out of it. But Gareth has no regrets at all about his choice of base vehicle, and there’s nothing significant he says he’d do differently. ‘If I don’t like it now or it no longer works for me,’ he says, ‘I just change it.’ Us humans may be fickle but, if ever there were such a thing, that’s definitely Landy Loyalty.